Hurricane Hunter aircraft fly into the belly of the beast

Hurricane Hunter aircraft fly into the belly of the beastThe (Fort Myers, Fla.) News-Press flew on the Hurricane Hunter Friday as Gustav developed from a youthful tropical storm into a mature, powerful hurricane with devastating potential to life and property.

During the Hurricane Hunter's flight we watched and spoke with the six-member crew, learned about their individual jobs, and rode in the cockpit with the pilots and navigator. Most of all, we broke through the roiling winds of the eye wall four times, to fly across its broad expanse and back out again.

The Hunter's wild and dangerous ride provides continuous, precise measurements of atmospheric conditions to the National Hurricane Center.

That allows the center, in turn, to more accurately predict the hurricane path and pinpoint specific areas that will have to issue mandatory evacuation orders. Increased accuracy saves unnecessary evacuation costs and the nerves of people who otherwise might have to leave their homes.

For most of the hunters, this is what they live for and are willing to die for. They have no parachutes, since it would be foolhardy to jump to safety amid hurricane winds. It's better to ditch the plane and rely on life vests, lifeboats and prayer to survive the high seas below.

The 53rd Weather Reconnaissance Squadron of the Air Force Reserve, a one-of-a kind unit flying into tropical storms and hurricanes since 1944, operates the Hunter.

The reservists are part of the 403rd Wing based at Keesler Air Force Base in Biloxi, Miss.

But Friday we flew from Homestead Air Reserve Base. When we began the flight at 11:15 a.m., Gustav's winds started off at 65 mph.

During the 10 1/2-hour flight, Gustav strengthened to a Category 1 hurricane at about 83 mph. Since we landed at 9:45 p.m. Friday, the storm has catapulted to a Category 4 hurricane at 150 mph.

Fasten your seat belts. It's going to be a bumpy ride.

8:30 a.m.: Meet the boss

We get to Homestead well before our designated arrival time and have a chance to speak with Maj. Jeff Ragusa, the deployed mission commander in charge of all hurricane operations flying from Homestead.

Nobody flies at the top of a hurricane, Ragusa said. "They want to know what happens at the bottom of it. If (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) had its way, we'd fly four feet above the water."

Instead we're flying at 10,000 feet to find the maximum and most dangerous winds. The Hunter is a WC-130J aircraft, a newer model of the C-130, newly equipped with the Stepped-Frequency Microwave Radiometer, dubbed SMURF. The technology allows the Hurricane Hunters to constantly measure surface winds directly below the aircraft and helps increase the accuracy of the National Hurricane Center's forecasts by 30%.

The storm's circulation is already counter-clockwise, but no well-formed eye is apparent yet, Ragusa said. The Hunter's target is the western tip of Jamaica. We have to fly over Cuba to get there, and the State Department has to secure overflight permission from the Cuban government to do it.

The plane will fly in an X or Alpha pattern, going 105 miles out from the outskirts of the storm to its center, then back out again, repeating the pattern for all four quadrants of the storm.

"Every ride is a bumpy ride," Ragusa said. "As you walk through the aircraft, always keep an eye out for something to grab onto."

"And just remember, air sickness is just part of flying," said Lt. Col. Tom Davis, spokesman for Homestead Air Reserve Base.

9:25 a.m.: The briefing

Ragusa introduces the six-member crew at his pre-flight. They are:

• Lt. Col. C. Floyd Plash, aircraft commander and pilot

• Capt. Nate Gasscock, a pilot

• Lt. Col Dan Jones, pilot

• Capt. Eileen Bundy, aerial reconnaissance weather officer

• Mike Anderson, navigator

• Sgt. Major Justin Jones, the dropsonde system operator

The dropsonde is the major measurement instrument the crew uses to send information directly to the National Hurricane Center, like air pressure, wind speed and other data. The instrument is a small cylindrical device with a parachute on the end.

Once released from bottom of the aircraft, it floats down 2,500 feet a minute and sends back radio data, Jones said.

11:05 a.m.: Takeoff

The plane is massive, with the ability to plow through winds at more than 370 mph. But the storm is bigger.

The inside of the Hunter is like a giant, stripped-down tin can.

Its wiring and insulated pipes can be seen in the ceiling. The seats are simply red canvas benches lining either side of the plane with a back of red webbing — something to hang onto.

All the cargo is tied down, including cardboard boxes full of the dropsondes. Sgt. Major Justin Jones pulls out five of them in preparation, large cardboard cylinders wrapped in foil and pink bubble wrap.

The plane vibrates in place with its brakes on, as the four propeller engines are revved. Then it lurches forward at full speed on the bumpy runway.

The claw-like propellers become a blur. The noise inside is a steady, high-pitched hum. Davis distributes ear plugs.

The black nose cone lifts into the air.

Like a flight attendant, Jones signals the location of air sickness bags in little brown envelopes. He pulls one out and demonstrates the procedure.

The bathroom is at the back of the plane behind a green curtain.

1:25 p.m.: The flight

The Hurricane Hunter flies for about two hours, straight across the olive-green landscape of Cuba. The plane cuts between the cities of Cabaiguan and Moron, just skirting the city of Ciego De Avila.

As we come off the coast and head for Jamaica, just off Montego Bay, the turbulence starts. The massive WC-130J is buffeted like a toy, and the drops in altitude are sudden — about 200 feet at a time.

Jones ejects the dropsondes from the plane about every five minutes. Each one is tracked by a satellite frequency, its progress displayed by a colored graph on his computer monitor.

He said they cost $700 each, but the cost is worth the data they provide and the lives they save.

The hunter gets six different views of radar from cameras providing different angles. Another screen displays what all four engines are doing, from horsepower to oil pressure.

Above the emergency exit to the right of Jones' computer console is a sign that reads: "Ground and ditching use only."

The eye

The plane shakes and begins to go from side to side. We must be penetrating the eye wall for the first time, the roughest point of the trip.

Davis calmly munches on crackers from a plastic sandwich bag, then kicks back and closes his eyes for a few minutes.

The hurricane eye almost defies description by the human eye.

The eye may be the center of a deadly force of destruction, but witnessing its scope and majesty inspires awe. The massive ring of clouds forms the banks of a wide, empty lake of nothingness, save for a few scudding clouds.

Other images flood the mind: A white-coiled snake ready to strike. The crater of a volcano with puffs of cloud floating like steam. You can see through them below to the boiling blue lava of a stormy sea.

The eye changed each time we flew through it. At first its curve remained raggedy and incomplete. Then it formed into a rough circle about 25 miles across. By the forth and final pass-through, it became more defined — a smaller, tighter circle.

"Is that the eye wall? It had an inner spiral the last time. This could be the same thing," said Lt. Col. C. Floyd Plash, the mission commander, as the Hunter made the final pass-through at 7 p.m.

"Yeah, that's it," said Capt. Nate Gasscock, the pilot sitting beside him.

The job done —until their next shift 18 hours later, we flew home.

As the storm strengthens, the crews' shifts will shorten to six hours, then three hours round-the-clock instead of the standard 8-10 hours, said Lt. Col. Dan Jones, a pilot.

Why fly?

The crewmembers have different reasons for being here. They include patriotism, fulfilling a long-held dream, trying to conquer a childhood fear of severe weather or simply working near the place where their families live.

"Growing up, I was one of those kids who was afraid of weather," said Capt. Eileen Bundy, aerial reconnaissance weather officer.

So she went into meteorology and ended up flying into hurricanes, "making my mom real happy," she joked.

"It's getting pretty personal to me," Gasscock said. His wife as well as other families of crewmembers who live near the base in Biloxi will have to evacuate while they continue to fly.

But Gasscock knows the work is important to keep their families as well as hundreds of thousands of other residents safe.

When asked his motivation for being a Hurricane Hunter, Gasscock pointed to his jumpsuit sleeve where an American flag patch was sewn on. "Right there," he said.

LATEST TRACK ON HANNA

|

Ike strengthens into major hurricane

By Joseph Guyler Delva

PORT-AU-PRINCE (Reuters) - Hurricane Ike strengthened rapidly into a major Category 3 hurricane in the open Atlantic on Wednesday and Tropical Storm Hanna intensified to a lesser degree as it swirled over the Bahamas toward the southeast U.S. Coast.

Hanna's torrential rains had already submerged parts of Haiti, stranding residents on rooftops and prompting President Rene Preval to warn of an "extraordinary catastrophe" to rival a storm that killed more than 3,000 people in the flood-prone Caribbean country four years ago.

Hanna was forecast to move over the central and northern Bahamas on Thursday, strengthening back into a hurricane with winds of at least 74 mph (119 kph) before hitting the U.S. coast near the North Carolina-Virginia border on Saturday.

Ike posed no immediate threat to land but strengthened explosively, growing in the space of a few hours from a tropical storm to a "major" Category 3 hurricane on the five-step Saffir-Simpson intensity scale.

Ike had top sustained winds of 115 mph (185 kph) as it swept across the open Atlantic 645 miles (1,035 km) east-northeast of the Leeward Islands, the U.S. National Hurricane Centre said.

It was forecast to strengthen further as it moved toward the southern Bahamas early next week but it was too early to tell whether it would threaten land, the forecasters said.

Tropical Storm Josephine also marched across the Atlantic on a westward course behind Ike but it had begun to weaken.

The burst of storm activity follows Hurricane Gustav, which slammed into Louisiana near New Orleans on Monday after a course that also took it through Haiti, where it killed more than 75 people.

The storms were troubling news for U.S. oil and natural gas producers in the Gulf of Mexico and for the millions of people living in the Caribbean and on America's coasts.

The U.S. government has forecast 14 to 18 tropical storms will form during the six-month season that began on June 1, more than the historical average of 10. Josephine was already the 10th of the year, forming before the statistical peak of the season on September 10.

The record-busting 2005 season, which included deadly Hurricane Katrina, had 28 storms.

'REALLY CATASTROPHIC'

In Haiti, officials were still counting the scores of people killed by Gustav when Hanna struck the impoverished nation on Monday night.

Authorities said Hanna caused flooding and mudslides that killed at least 61 people across Haiti, including 22 in the low-lying port of Gonaives. The death toll was expected to rise as floodwaters receded and rescuers reached remote areas.

"We are in a really catastrophic situation," said Preval, who planned to hold emergency talks with representatives of international donor countries to appeal for aid.

"It is believed that compared to Jeanne, Hanna could cause even more damage," he said, referring to a storm that sent floodwaters and mud cascading into Gonaives and other parts of Haiti's north and northwest in September 2004, killing more than 3,000 people.

Gonaives residents were still stranded on their rooftops two days after the floodwaters rose and the government did not know the fate of those who had been in hospitals and prisons.

"There are a lot of people on rooftops and there are prisoners that we cannot guard," Preval said.

Hanna had hovered off Haiti's coast since Monday, drowning crops in a desperately poor nation already struggling with food shortages. It also triggered widespread flooding in the neighbouring Dominican Republic.

The Miami-based hurricane centre said Hanna had begun moving northward and its top winds strengthened slightly to 65 mph (105 kph). It was forecast to turn northwest across the central and northern Bahamas in the next two days and then hit the U.S. coast in North Carolina and the mid-Atlantic states on Saturday.

It was too early to say where Ike might go, after it churns through the Caribbean, but the storm has drawn the attention of energy companies running the 4,000 offshore platforms in the Gulf of Mexico that provide the United States with a quarter of its crude oil and 15 percent of its natural gas.

By late Wednesday, Josephine was swirling over the far eastern Atlantic about 375 miles (605 km) west of the Cape Verde Islands. It was moving west but had begun to weaken, with top sustained winds dropping to 60 mph (95 kph).

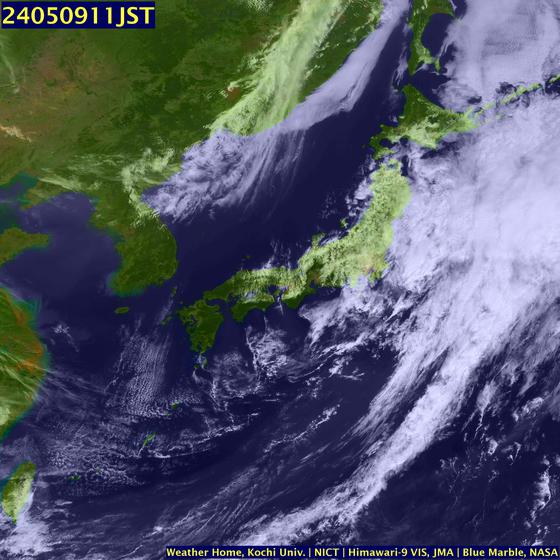

LATEST IMAGES ON IKEEnhanced Infrared Satellite Image of Hurricane Ike:

Infrared Satellite Image of Hurricane Ike:

Visible Satellite Image of Hurricane Ike:

Water Vapor Satellite Image of Hurricane Ike:

Shortwave Satellite Image of Hurricane Ike:

Dvorak Satellite Image of Hurricane Ike:

RS

![Validate my RSS feed [Valid RSS]](valid-rss.png)