JPL says: FORGET LA NINA: OSCILLATION RULES AS THE PACIFIC COOLS

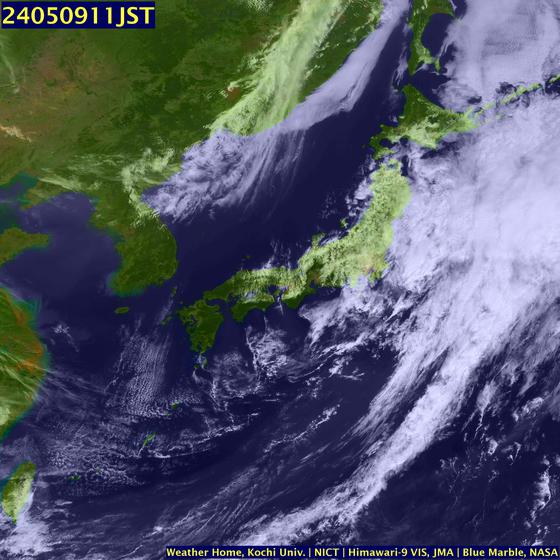

JPL says: FORGET LA NINA: OSCILLATION RULES AS THE PACIFIC COOLSPASADENA, Calif. — The latest image of sea-surface height measurements from the U.S./French Jason-1 oceanography satellite shows the Pacific Ocean remains locked in a strong, cool phase of the Pacific Decadal Oscillation, a large, long-lived pattern of climate variability in the Pacific associated with a general cooling of Pacific waters. The image also confirms that El Niño and La Niña remain absent from the tropical Pacific.

he image is based on the average of 10 days of data centered on Nov. 15, 2008, compared to the long-term average of observations from 1993 through 2008. In the image, places where the Pacific sea-surface height is higher (warmer) than normal are yellow and red, and places where the sea surface is lower (cooler) than normal are blue and purple. Green shows where conditions are near normal. Sea-surface height is an indicator of the heat content of the upper ocean.

The Pacific Decadal Oscillation is a long-term fluctuation of the Pacific Ocean that waxes and wanes between cool and warm phases approximately every five to 20 years. In the present cool phase, higher-than-normal sea-surface heights caused by warm water form a horseshoe pattern that connects the north, west and southern Pacific. This is in contrast to a cool wedge of lower-than-normal sea-surface heights spreading from the Americas into the eastern equatorial Pacific. During most of the 1980s and 1990s, the Pacific was locked in the oscillation’s warm phase, during which these warm and cool regions are reversed. For an explanation of the Pacific Decadal Oscillation and its present state, see: http://jisao.washington.edu/pdo/ and http://www.esr.org/pdo_index.html

Sea-surface temperature satellite data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration mirror Jason sea-surface height measurements, clearly showing a cool Pacific Decadal Oscillation pattern, as seen at: http://www.cdc.noaa.gov/map/images/sst/sst.anom.gif

“This multi-year Pacific Decadal Oscillation ‘cool’ trend can cause La Niña-like impacts around the Pacific basin,” said Bill Patzert, an oceanographer and climatologist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif. “The present cool phase of the Pacific Decadal Oscillation will have significant implications for shifts in marine ecosystems, and for land temperature and rainfall patterns around the Pacific basin.”

According to Nathan Mantua of the Climate Impacts Group at the University of Washington, Seattle, whose research contributed to the early understanding of the Pacific Decadal Oscillation, “Even with the strong La Niña event fading in the tropics last spring, the North Pacific’s sea surface temperature anomaly pattern has remained strongly negative since last fall. This cool phase will likely persist this winter and, perhaps, beyond. Historically, this situation has been associated with favorable ocean conditions for the return of U.S. west coast Coho and Chinook salmon, but it translates to low odds for abundant winter/spring precipitation in the southwest (including Southern California).”

Jason’s follow-on mission, the Ocean Surface Topography Mission/Jason-2, was successfully launched this past June and will extend to two decades the continuous data record of sea surface heights begun by Topex/Poseidon in 1992. The new mission has produced excellent data, which have recently been certified for operational use. Fully calibrated and validated data for science use will be released next spring.

JPL manages the U.S. portion of the Jason-1 mission for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, Washington. JPL is managed for NASA by the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena.

WEATHER NOTENew hurricane chief restores the calm after in-house storm

Bill Read didn't ride into town with both guns blazing. But in his own quiet way, he did restore order.

For much of last year, the National Hurricane Center was in turmoil, following a staff revolt against then-director Bill Proenza. Congress feared the discord might hurt forecasts, and the normally staid institution was thrust into controversy.

Today, that episode has all but subsided, and the center has refocused on tracking tropical systems. Insiders credit Read, the new director, with soothing frayed nerves and rebuilding chemistry.

"Bill knows it's not all about one man, it's not all about the director," said Max Mayfield, the popular former director of the center. "In that way, he's very much like me."

Senior hurricane specialist Lixion Avila described the atmosphere inside the hurricane center these days as "very nice."

"The most important thing is that every time we make a decision, we make it together as a team," Avila said. "He listens to the specialists, and we listen to him."

Intimidation and warning

Read, 59, a National Weather Service veteran forecaster and manager, was recruited to be the center's acting deputy director in August 2007.

That was after Proenza alienated the staff, both by intimidating employees and warning that the demise of a weather satellite would hurt storm predictions, according to an independent report.

Top management at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which oversees the hurricane center, removed him as director in July 2007. Proenza was returned to his former job as director of the Southern Region of the National Weather Service.

NOAA officials named Read as the hurricane center's director in January.

As a result of the Proenza ordeal, the center still is making adjustments, Read said. The management structure is being organized and consultants are working with employees to address lingering morale problems.

"That was a pretty traumatic event for the folks who worked here," Read said. "I don't think everyone's totally moved on from that event."

For the most part, he added, operations have returned to normal and forecasts were never compromised. That was evident over the course of the 2008 season, when specialists generated several on-target storm predictions, for instance with Hurricane Gustav, which hit near New Orleans.

"I'm happy with where we're at," Read said of his forecasting team's performance. "I'm very satisfied with the work ethic and the attention to detail."

Noting that his management style is rather low key, Read said he doesn't intend to make any major changes in the way the hurricane center does business. Rather, he is trying to restore a sense of calm at the center in southwest Miami-Dade County.

"More and more I'm going to be working on inputting my management style, which tends to be a calming influence," he said.

Boosting morale

In the past season, whenever storms emerged, Read made a point of watching over the shoulders of his forecasters as they worked up tropical predictions. He did so to learn the intricacies of hurricane forecasting as well as to boost the morale of his specialists.

"That way I know what's going on," he said. "They know I'm interested in what they're doing."

The ultimate goal, he said, is to improve forecast accuracy, particularly with intensity predictions, an area where the center has struggled. Considering no hurricanes pulled any major surprises, he said his first season as the hurricane center's director was a good one.

"We didn't have one of those Mother Nature gotcha moments, where the storm threw a curve at us in close," he said. "I got a good break-in year."

MARTIME NOTEDangerous waves like those aren't common, thankfully. A study of radar data from oil platforms estimated that merely 10 waves more than 75-feet-high appeared around the globe during one recent three-week period.

The bad news is that there's almost nothing that a cruise ship captain can do to either predict or avoid these waves, which rise up to five times as high as the waves around them. These rogue, or freak, waves appear to come from an angle that's out of sync with the wind and other sea waves. You'll occasionally find these waves out in the sea but also in near-beach areas, both in sandy and rocky shores. Lots of tragedies occur yearly all around the world.

To learn more about these waves, I did an e-mail interview with Paul C. Liu, who retired last year from his post as research physical oceanographer for NOAA and who blogs at Freaque Waves.

What should cruise passengers know about the frequency of dangerous waves, and exactly what type of waves are likely on the open seas?

I guess all kinds of waves are likely on the open seas, including freaque waves. They are not always happening. Most of the time they are not! But we just cannot rule out the fact that freaque waves can happen at any time and at any place. Cruise passengers should just be mindful that the possibility is there and continue to enjoy the cruise. Even if an encounter does happen, the damage will likely to be not extensive. The kind of fiction as shown in the movie Poseidon will not ever happen in real life!

What is a "freaque wave", what is its most typical origin or cause, and why do you use that nomenclature of "freaque" instead of using the term "rogue" or something more scientific sounding?

Freaque is a portmanteau word formed by the two frequently and synonymously used words of rogue and freak in describing the kind of unexpected and unpredictable waves. Many people in the scientific literature are fond of using the expression "freak or rogue waves." I choose to use "freaque waves" instead.

Are there any particular waters in particular regions that are known to be prone to freaque waves?

The short answer is no. Because of the conjecture that when ocean waves propagating into oncoming strong ocean current field might lead to the forming of large waves, regions along the Gulf stream in the North Atlantic, along the Agulhas currents in South Indian Ocean, and along the Kuroshio in Northwest Pacific, are thought to be prone of freaque waves. But areas that don't have strong ocean currents, such as the North Sea, can also have frequent freaque waves. So the talk of regional proneness is at most covering a part of the story.

What's the essential dispute about freaque waves in the scientific community? And is there something that makes scientists groan when they read accounts of waves striking cruise ships because the statements are misleading or hyperbolic or inaccurate?

Because the study of freaque waves is still relatively new, I don't think there is as yet any "essential dispute" per se in the scientific community. Lack of general consensus, maybe! Different scientists may have different concept of what "rare" or "frequent" means or using relatively different definitions for freaque waves. And there are may be different approaches to the problem. Some treats freaque waves as a part of the study of extreme waves whereas some others do not. (Freaque waves are always extreme waves, but not all the extreme waves are freaque waves!)

What's the most typical misunderstanding of the freaque wave issue, as you've encountered it when reading media reports or talking with others?

Oh yes, the media! I don't have much respect for the present day, so called, "main-stream" media. Here's an example—a paragraph from a New York Times article about freaque waves a couple of years ago:

Enormous waves that sweep the ocean are traditionally called rogue waves, implying that they have a kind of freakish rarity. Over the decades, skeptical oceanographers have doubted their existence and tended to lump them together with sightings of mermaids and sea monsters.

Rogue waves are known to happen momentarily. They appear out of nowhere. A wave takes place, and then disappears like nothing has happened. Waves like that never, yes, never, "sweep" the ocean. There is no such thing as "traditionally called rogue waves." Rogue wave is a fairly recent term. The use of the term "freak wave" was started by U.K. scientist Laurence Draper in 1964. There was no firmly established term before 1964. The existence of unusually large, great waves was nevertheless very much on the minds of every seagoing oceanographer. I don't think anyone in their right mind would "lump them together with sightings of mermaids and sea monsters." I just hope your readers beware of this kind of irresponsibility.

3 More days til Christmas!

RS

![Validate my RSS feed [Valid RSS]](valid-rss.png)