I post this article because it presents a interesting backgrounder on people in the marine salvage community.

I post this article because it presents a interesting backgrounder on people in the marine salvage community. A industry that many have either never heard of or do not understanding what marine salvage companies actually do or go through to get the job done.

They are truly first responders and sometimes the only responders.

High Tech Cowboys of the Deep Seas: The Race to Save the Cougar Ace

Latitude 48° 14 North. Longitude 174° 26 West.

Almost midnight on the North Pacific, about 230 miles south of Alaska's Aleutian Islands. A heavy fog blankets the sea. There's nothing but the wind spinning eddies through the mist.

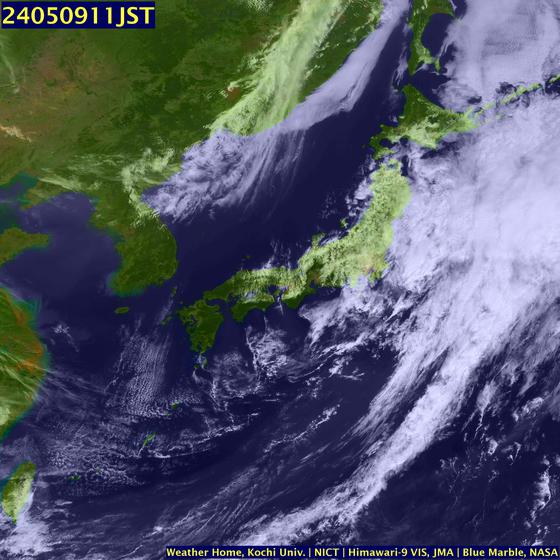

( Pix: The Cougar Ace lists at a precarious angle in Wide Bay, Alaska. Photo: Courtesy of US Coast Guard )

Out of the darkness, a rumble grows. The water begins to vibrate. Suddenly, the prow of a massive ship splits the fog. Its steel hull rises seven stories above the water and stretches two football fields back into the night. A 15,683-horsepower engine roars through the holds, pushing 55,328 tons of steel. Crisp white capital letters — COUGAR ACE — spell the ship's name above the ocean froth. A deep-sea car transport, its 14 decks are packed with 4,703 new Mazdas bound for North America. Estimated cargo value: $103 million.

On the bridge and belowdecks, the captain and crew begin the intricate process of releasing water from the ship's ballast tanks in preparation for entry into US territorial waters. They took on the water in Japan to keep the ship steady, but US rules require that it be dumped here to prevent contaminating American marine environments. It's a tricky procedure. To maintain stability and equilibrium, the ballast tanks need to be drained of foreign water and simultaneously refilled with local water. The bridge gives the go-ahead to commence the operation, and a ship engineer uses a hydraulic-powered system to open the starboard tank valves. Water gushes out one side of the ship and pours into the ocean. It's July 23, 2006.

In the crew's quarters below the bridge, Saw "Lucky" Kyin, the ship's 41-year-old Burmese steward, rinses off in the common shower. The ship rolls underneath his feet. He's been at sea for long stretches of the past six years. In his experience, when a ship rolls to one side, it generally rolls right back the other way.

This time it doesn't. Instead, the tilt increases. For some reason, the starboard ballast tanks have failed to refill properly, and the ship has abruptly lost its balance. At the worst possible moment, a large swell hits the Cougar Ace and rolls the ship even farther to port. Objects begin to slide across the deck. They pick up momentum and crash against the port-side walls as the ship dips farther. Wedged naked in the shower stall, Kyin is confronted by an undeniable fact: The Cougar Ace is capsizing.

He lunges for a towel and staggers into the hallway as the ship's windmill-sized propeller spins out of the water. Throughout the ship, the other 22 crew members begin to lose their footing as the decks rear up. There are shouts and screams. Kyin escapes through a door into the damp night air. He's barefoot and dripping wet, and the deck is now a slick metal ramp. In an instant, he's skidding down the slope toward the Pacific. He slams into the railings and his left leg snaps, bone puncturing skin. He's now draped naked and bleeding on the railing, which has dipped to within feet of the frigid ocean. The deck towers 105 feet above him like a giant wave about to break. Kyin starts to pray.

Jackson Hole, Wyoming, 4 am.

A phone rings. Rich Habib opens his eyes and blinks in the darkness. He reaches for the phone, disturbing a pair of dogs cuddled around him. He was going to take them to the river for a swim today. Now the sound of his phone means that somewhere, somehow, a ship is going down, and he's going to have to get out of bed and go save it.

It always starts like this. Last Christmas Day, an 835-foot container vessel ran aground in Ensenada, Mexico. The phone rang, he hopped on a plane, and was soon on a Jet Ski pounding his way through the Baja surf. The ship had run aground on a beach while loaded with approximately 1,800 containers. He had to rustle up a Sikorsky Skycrane — one of the world's most powerful helicopters — to offload the cargo.

Photo: Andrew Hetherington

Ship captains spend their careers trying to avoid a collision or grounding like this. But for Habib, nearly every month brings a welcome disaster. While people are shouting "Abandon ship!" Habib is scrambling aboard.

He's been at sea since he was 18, and now, at 51, his tanned face, square jaw, and don't even try bullshitting me stare convey a world-weary air of command. He holds an unlimited master's license, which means he's one of the select few who are qualified to pilot ships of any size, anywhere in the world. He spent his early years captaining hulking vessels that lifted other ships on board and hauled them across oceans. He helped the Navy transport a nuclear refueling facility from California to Hawaii. Now he's the senior salvage master — the guy who runs the show at sea — for Titan Salvage, a highly specialized outfit of men who race around the world saving ships.

MARTIME NOTES:

Messing About In Ships Podcast #12 - Special Interview of US Coast Guard Rescue of Sailors Aboard the Yacht Sean Seymour II

Here is the inspiring interview with the US Coast Guard helicopter rescue crew that saved the lives of three sailors aboard the yacht Sean Seymour II.

File Download:Messing About In Ships 12 - Special Interview

Interviewees:

- Aviation Survival Technician Second Class Drew D. Dazzo, H-60 Rescue Swimmer

- Lieutenant Commander Nevada A. Smith, H-60 Aircraft Commander

- Lieutenant Junior Grade Aaron G. Nelson, H-60 Copilot

- Aviation Maintenance Technician Second Class Scott D. Higgins, H-60 Flight Mechanic

Final log entry by Jean Pierre de Lutz, owner of Sean Seymour II

Robin Storm blog: Saved from the Angry Atlantic

Watch for future episodes with interviews with the C130 flight crew and the Sean Seymour II captain/owner.

RS

![Validate my RSS feed [Valid RSS]](valid-rss.png)