We have reviewed what a EPIRB is and how it communicates between the vessel or person in trouble and we reviewed how the EPIRB communicates with the overhead satellites to the rescuers.

I have begun this story in this fashion because many of the visitors to this site are not mariners and its important for them to understand some of the technology and why when something like a EPIRB goes astray, its important to get to the bottom of the failure.

Today I want to not just revisit or go "back to the future" and remember just what took place prior to setting sail, but also what took place during the emergency.

To do this lets first revisit the final log of the s/v Sean Seamour II.

Cape Cod, May 12th 2007

This is the log of actions and events driven by the only subsequently named Sub-tropical Storm Andrea, leading to the sinking of s/v Sean Seamour II and the successful rescue of its entire crew on the early morning of May 7th 2007.

We departed from Green Cove Springs on the Saint Johns River in the early morning of May 2nd, 2007. Gibraltar was our prime destination with a planned stopover in the Azores for recommissioning and eventually fuel. The vessel, on its second crossing was fully prepared and some of the recent preparations done by Holland Marine and skipper with crew were as follows:

· Full rig check, navigation lights, new wind sensor, sheet and line check / replacement.

· New autopilot, stuffing box and shaft seal, house battery bank, racor fuel filtering system.

· Bottom paint, new rudder bearing and check, new auxiliary tiller, full engine maintenance.

· Recertification of life raft and check of GPIRB (good to November 2007), update and replacement of all security equipment (PFDs, flares, medical, etc).

Although paper charts were available for all planned destinations, with increased dependence on electronic navigational aids, two computers were programmed to handle both the MaxSea navigation software (version 12.5) as well as the Iridium satphone for weather data (MaxSea Chopper and OCENS). A full electronic systems checkout and burn trial was done during the days prior to departure.

For heavy weather and collision contingencies cutter rigged Sean Seamour II was equipped with two drogues (heavy and light), collision mat, auxiliary electric pump, as well as extensive power tools to enable repairs at sea with the 2.4kva inverter. Operational process and use of this equipment was discussed at length with the crew in anticipation. Other physical process contingencies such as lashing, closing seacocks, companionway doors, etc. were equally treated.

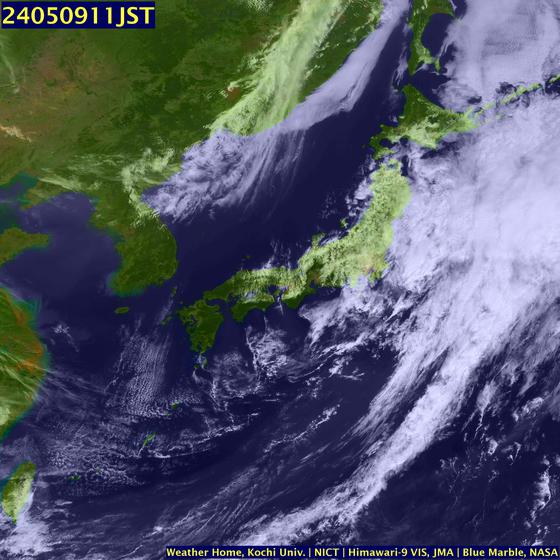

The 7 day weather GRIBs downloaded almost daily from April 25th onwards showed no inconsistencies, with the two high and two low pressure systems fairly balanced over the western Atlantic. Only the proximity of the two low pressure systems seemed to warrant surveillance as the May 5th GRIB would indicate with a flow increase from the N,NO from 20 to 35 knots focused towards coastal waters.

Already on a northerly course some 200 nautical miles out, I maintained our navigational plan with a N,NE heading until increased winds warranted a more easterly tack planned approximately 300 nautical miles north of Bermuda towards the Azores.

Wind force increased about eight hours earlier than expected and later shifted to the NE reaching well into the 60 knots range by early afternoon, then well beyond as the winds shifted. Considering that we were confronted with a sustained weather system that was quite different from the gulf stream squall lines we had weathered previous days, by mid afternoon I decided to take appropriate protective measures.

From our last known position approximately 217 nautical miles east of Cape Hatteras I reversed course, laying my largest drogue off the starboard stern while maintaining a quarter of the storm jib on the inner roller furl. This was designed to balance the boat's natural windage due in large part to its hard dodger and center cockpit structure. By late afternoon the winds were sustained at well over 70 knots and seas were building fast. I estimate seas were well into 25 feet by dusk but after adding approximately 150 feet of drogue line the vessel handled smoothly over the next eight hours advancing with the seas at about 6 knots (SOG). By late evening the winds were sustained above 74 kts and a crew member recorded a peak of 85.5 kts.

By late afternoon the winds were sustained at well over 70 knots and seas were building fast. I estimate seas were well into 25 feet by dusk but after adding approximately 150 feet of drogue line the vessel handled smoothly over the next eight hours advancing with the seas at about 6 knots (SOG). By late evening the winds were sustained above 74 kts and a crew member recorded a peak of 85.5 kts.

Growing and irregular seas were the primary concern as in the very early hours of the morning the boat was increasingly struck by intermittent waves to its port side. Crew had to be positioned against the starboard side as both were tossed violently across the boat. Water began to accumulate seemingly fed through the stern engine-room air cowls. I believe in retrospect the goosenecks were insufficient with the pitch of larger waves as they were breaking onto the stern.

At approximately 02.45 hours we were violently knocked all the way down to starboard. It appears that the resulting angle and tension may have caused the drogue line to rupture (clean cut), perhaps as it rubbed against the same engine-room air-intake cowl positioned just below the cleat. The line was attached to the port side main winch then fed through the cleat where it was covered with anti-chaffing tape and lubricant. Before abandoning ship I noticed the protected part of the line was intact and extended beyond the cleat some five inches. Its position in the cleat rather than retracted from it also supports this theory.

After the knockdown I knew there was already structural damage and that we had lost control of the vessel. I pulled the GPIRB (registered to USCG documented Sean Seamour II) but I suspect that the old EPIRB from 1996 (Registered to USCG documented Lou Pantaï, but kept as the vessel was sold to an Italian national in 1998) might have been automatically launched first. I kept this unit as a redundancy latched in its housing on the port side of the hard dodger; it may have been ejected upon the first knockdown as Coast Guard Authorities questioned relatives with this vessel name versus Sean Seamour II. Herein lies a question that needs to be answered, hopefully it will be in light of the USCG report.

The GPIRB initially functioned but the strobe stopped and the intensity of the light diminished rapidly to the extent that I do not know if the Coast Guard received that signal. At the time were worried the unit was not emitting and I re initiated the unit twice. The unit sent for recertification with the life raft a few weeks prior had been returned from River Services. They had responded to Holland Marine that the unit was good until this coming November, functioned appropriately, and that the battery had an extra five year life expectancy. I will await reception of the Coast Guard report to find out if one or both signals was processed as all POCs were questioned regarding Lou Pantaï and not my current vessel Sean Seamour II (both vessels had been / in the case of Sean Seamour II is US Coast Guard documented).

Expecting worse to come I re-lashed and locked all openings and the companionway. At 02:53hours we were struck violently again and began a roll to 180 degrees. As the vessel appeared to stabilize in this position I unlocked the companionway roof to exit an see where the life raft was. It had disappeared from its poop deck cradle which I could directly access as the helm and pedestal had been torn away. When I emerged to the surface against the boat's starboard (in righted port position) it began its second 180 degree roll. As it emerged the rig was almost longitudinal to the boat barely missing the stern arch. Spreaders were arrayed over cockpit and port side, mast cleanly bent at deck level, fore stays apparently torn away.

I ordered the crew to start all pumps. By their own volition they also cut out 2.5 gallon water bottles to enable physical bailing while I continued to locate the life raft. It finally appeared upside down under the rig. As its sea anchors and canopy lines were entangled in the rig and partially torn by one of the spreaders I decided to cut them away in an effort to save time and effort. I needed the crew below and had to manage the rig entanglement alone. This done I managed to move the unit forward and use its windward position to blow it over the bow to starboard, attaching it still upside down.

Below, water was being stabilized above the knees. The new higher positioned house battery bank was not shorted by the water level but the engine bank was flooded not enabling us to start the engine and pump from the bilge instead of the seacock. In retrospect this was not a loss as having to keep one of the companionway doors off for bailing and to route the Rule pump pipe, the water pouring in from here and the through-deck mast hole were no match for the impeller' volume. Plugging the mast passage was also not a solution as it was moving and hitting violently against the starboard head wall and was dangerous to try to cope with.

I knew the situation was desperate but it was still safer to stay aboard than to abandon ship, let alone in the dark any earlier than necessary. Estimating daylight at about 05:30 hours, we needed to hold on for at least another two hours. As the boat shifted in the waves it became increasingly vulnerable to flooding from breaking waves. One such wave at about 05:20 added about 18 inches of water, as the bow was now barely emerged these two factors triggered my decision to abandon ship. I exited first knowing that the raft was still upside down. In addition, some of the canopy lines still needed to be cut from the rig entanglement. In the precipitation the grab bag containing Iridium phone, VHF, GPS and all our personal and ship documents was lost.

As we boarded the now upturned raft it immediately flooded with the breaking waves and once unprotected from the wind by the hull structure was prone to turn over (no sea anchors nor canopy to roll over on). Hypothermia was already gaining upon one of my crew and myself and our efforts to right and re-enter the raft drained strength. Periods spent lying on the overturned raft exposed to the wind seemed to further weaken us.

Sean Seamour II sank a few minutes after we abandoned ship fully disappearing from view after the second wave crest.

We became aware of fixed wing overflight sometime between 06:00 and 07:00 hours and estimate that the Coast Guard helicopter arrived some time around 08:30 hours. As seemingly the most affected by hypothermia and almost unconscious the crew had me lifted out first. It was a perilous process during which Coast Guard AST2 Dazzo was himself injured (later to be hospitalized with us). The life raft was destroyed and abandoned by AST2 Dazzo as the third crew member was extracted. He also recouped the GPIRB which remained in USCG custody.

We became aware of fixed wing overflight sometime between 06:00 and 07:00 hours and estimate that the Coast Guard helicopter arrived some time around 08:30 hours. As seemingly the most affected by hypothermia and almost unconscious the crew had me lifted out first. It was a perilous process during which Coast Guard AST2 Dazzo was himself injured (later to be hospitalized with us). The life raft was destroyed and abandoned by AST2 Dazzo as the third crew member was extracted. He also recouped the GPIRB which remained in USCG custody.The emotions and admiration felt by my crew and myself to the dedication of this Coast Guard team is immeasurable, all the more so when hearing them comment on the severity and risk of the extraction, perhaps the worst they had seen in ten years (dixit SAT2 Dazzo). They claim to have measured 70 plus foot waves which from our perspective were mountains. We measured after the first knockdown and before loosing our rig winds still in excess of 72 knots.

Also to be commended are the medical teams involved, from our ambulatory transfer of custody from the rescue.

Redundancy;

"My paper chart set was second to few recreational mariners, just there my replacement budget would total 3000$, even though I had comprehensive sets of electronic charts MapMedia, C-Map plus Maptech.

As a redundancy freak (ended up saving the crew) I usually had three of everything if not more (three sets of belts, ten fuel filters, extra propeller, extra running rigging) if Sean Seamour II ran well through the storm is in part due to to low waterline weighted with extra equipment, from sailrite sewing machine to heavy tools sets. Safety wise, I consider I had everything essential plus."

The Facts

As you can see the Master of the s/v Sean Seamour II painstakingly pre-planed for his voyage but to his luck his redundancy of equipment paid off and save both his and his crews lives.. This is important to establish that the Master of the s//v Sean Seamour II did everything he should have done to ensure the safety of not just his vessel but his crew as well.

Now let's review some of the reported facts in this case and make note of, "Re-certification of life raft and check of GPIRB (good to November 2007)." The ACR Globalfix"406EPIRB in question was re-certified as being in compliance and in good working order by a certified outside vendor.

The ACR Globalfix" 406EPIRB in question was purchased in October of 2002 and the UK vendor registered it with NOAA and supplied it to the s/v Sean Seamour II at the time still in the Mediterranean. This EPIRB was always kept in its cradle affixed to the inside of the companionway whenever the boat was in use.

Prior to leaving for the May crossing back to Europe the s/v Sean Seamour II had a shipyard send the EPIRB with the life raft for re-certification, the accredited service center informed the Master through the yard that the unit was fully operational and certified until next November.

The EPIRB started to function normally when initiated at about 02:45hours on the 7th, between the knockdown of the s/v Sean Seamour II, its crew and the EPIRB, it was put back in its cradle for safekeeping and accessibility should the need to abandon ship occur, less than 30 minutes later it reportedly ceased functioning.

The Coast Guard received the signal initially, but the hexadecimal code it received was that of another vessel in Alabama. The USCG never received a distress signal from the s/v Sean Seamour II as there appears to have been no Sean Seamour II vessel registered in their database.

Once the USCG ascertained that the ID code received was that of a non initiated EPIRB, under the principle that every EPIRB has a unique hexadecimal code plus the interruption of the signal, further search on this distress signal was abandoned.

Had the Master of the s/v Sean Seamour II not kept an 11 year old EPIRB (another ACR 406 with its original battery that functioned over ten hours) from one of his prior vessels the crew would be yet another set of lost at sea statistics and all of the above would not be known.

How this happened is now under investigation by the USCG and the Master of the Sean Seanour II. But the ramifications of such a failure do impact the entire maritime community.

As of this writing I cannot stress enough that all mariners must ensure that their EPIRBs are not just in operational condition, that the registration matches the face plate on their EPIRBs, but also that the registration actually matches the hexadecimal code in the NOAA database.

For the s/v Sean Seamour II Lessons Learned visit the maritime communities best of the best gCaptain.com

RS

Previous Posts;

WebExclusive EPIRBs and the s/v Sean Seamour II - Part II

EPIRBs and the s/v Sean Seamour II

NHC Report on Subtropical Storm Andrea

Cheating Death On The High Seas

The s/v Sean Seamour II & The Hatteras Trench

High Sea's Update On Sean Seamour II

The Story of the Sailing Vessel Sean Seamour II

![Validate my RSS feed [Valid RSS]](valid-rss.png)