Missing radioactivity in ice cores bodes ill for part of Asia

Missing radioactivity in ice cores bodes ill for part of AsiaWhen Ohio State glaciologists failed to find the expected radioactive signals in the latest core they drilled from a Himalayan ice field, they knew it meant trouble for their research.

But those missing markers of radiation, remnants from atomic bomb tests a half-century ago, foretell much greater threat to the half-billion or more people living downstream of that vast mountain range.

It may mean that future water supplies could fall far short of what's needed to keep that population alive.

In a paper just published in Geophysical Research Letters, researchers from the Byrd Polar Research Center explain that levels of tritium, beta radioactivity emitters like strontium and cesium, and an isotope of chlorine are absent in all three cores taken from the Naimona'nyi glacier 19,849 feet (6,050 meters) high on the southern margin of the Tibetan Plateau.

"We've drilled 13 cores over the years from these high-mountain regions and found these signals in all but one - this one," explained Lonnie Thompson, University Distinguished Professor of Earth Sciences at Ohio State.

The absence of radioactive signals in the top portion of these cores is a critical problem for determining the age of the ice in the cores. The signals, remnants of the 1962-63 Soviet Arctic nuclear blasts and the 1952-58 nuclear tests in the South Pacific, provide well-dated benchmarks to calibrate the core time scales.

"We rely on these time markers to date the upper part of the ice cores and without them, extracting the climate history they preserve becomes more challenging," Thompson said.

"We drilled three cores through the ice to bedrock at Naimona'nyi in 2006," said Natalie Kehrwald, a doctoral student at Ohio State and lead author on the paper. "When we analyzed the top 50 feet (15 meters) of each core, we found that the beta radioactivity signal was barely above normal background levels."

Tritium, an isotope of hydrogen, and chlorine-36 were also both absent from the Naimona'nyi cores, she said. They were able, however, to find a small amount of a lead isotope, lead-210, which allowed them to date the top of the core.

"We were able to get a date of approximately 1944 A.D.," Kehrwald said, "and that, coupled with the other missing signals, means that no new ice has accumulated on the surface of the glacier since 1944," nearly a decade before the atomic tests.

While the loss of the radioactive horizons to calibrate the cores poses a challenge for Thompson's research, he worries more about the possibility that other high-altitude glaciers in the region, like Naimona'nyi, are no longer accumulating ice and the impact that could have on water resources for the people living in these regions.

"When you think about the millions of people over there who depend on the water locked in that ice, if they don't have it available in the future, that will be a serious problem," he said.

Seasonal runoff from glaciers like Naimona'nyi feeds the Indus, the Ganges and the Brahmaputra rivers in that part of the Asian subcontinent. In some places, for some months each year, those rivers are severely depleted now, the researchers said. The absence of new ice accumulating on the glaciers will only worsen that problem.

"The current models that predict river flow in the region have taken recent glacial 'retreat' into account," said Kehrwald, "but they haven't considered that some of these glaciers are actually thinning until now.

"If the thinning isn't included, then whatever strategies people adopt in their efforts to adapt to reductions in river flow simply won't work."

Thompson fears that what's happening to the Naimona'nyi glacier may be happening to many other high-altitude glaciers around the world. "I think that this has tremendous implications for future water supplies in the Andes, as well as the Himalayas, and for people living in those regions."

The absence of the radioactive signals in the 2006 Naimona'nyi core also suggests that Thompson and his colleagues have been lucky with their previous expeditions to other ice fields.

"We have to wonder -- if we were to go back to previous drill sites, some drilled in the 1980s, and retrieved new cores -- would these radioactive signals be present today?" he asked.

"My guess is that they would be missing." The researchers' recent work has shown similar thinning on glaciers in Africa, South America and in Asia in the past few years.

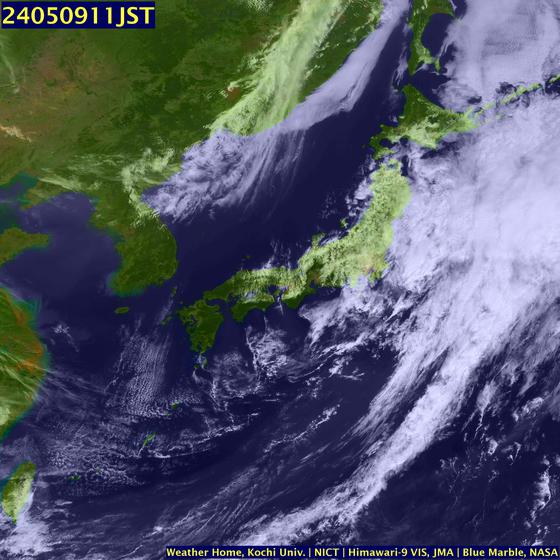

WEATHER NOTE

Maritimes didn't escape hurricanes this year

The Maritime provinces were hit with the remnants from various tropical storms and hurricanes this year, even though there was a less than normal number of named storms moving up the Atlantic Coast in 2008.

In some cases, the effect was no more than light rain, but in others, it was heavy rainfall fanned by gale-force winds.

It was the remnants from hurricanes Hanna and Kyle, both of which occurred in September, that brought the most severe weather conditions for New Brunswick, said Alex Sosnowski of State College. Pa., a spokesman for the AccuWeather.com Hurricane Centre.

Sosnowski said not all of the tropical storms moved into the province from the Atlantic Coast. He said some of them made their way inland, were re-energized by the Great Lakes and then, proceeded to head eastward, entering New Brunswick from the west.

The hurricane season officially runs from June 1 to the end of November, although you can sometimes get them later, such as occurred in 2005.

To be designated a name, a disturbance has to make it at least to tropical storm status. A tropical storm represents the level of severity immediately below that of a hurricane.

Sosnowski said hurricanes are rated in terms of intensity from Category 1 to Category 5 on the five-step Saffir-Simpson scale. Any of them ranking between Category 3 and 5 are considered to be major hurricanes with tremendous destructive capacity, he said.

Last year, he said there were 15 named storms, six of which reached hurricane status.

In the spring of this year, Sosnowski said the team of hurricane experts at Colorado State University predicted that there would also be 15 named storms this year, but that eight of them would graduate to hurricane status.

And they appear to have hit the nail just about on the head, said the AccuWeather.com meteorologist. To this point, he said there have been 16 named storms, eight of which became hurricanes.

Sosnowski said the last tropical storm this year was Paloma, which was a Category 4 hurricane. He said it strengthened rapidly and slammed into Cuba a few weeks ago, causing significant damage in much of that country.

The strength of high pressure over the Atlantic this year "pushed everything to the left," he said. As a result, he added, a lot of named storms ended up swinging into the Gulf of Mexico or south toward Central America.

Sosnowski anticipated there was little chance of another tropical storm developing the rest of this year.

This time of the year, he explained, there are significant wind shears that rip the tops off tropical disturbances before they can get a chance to develop into a storm or hurricane.

Rogue Waves: They're Real, & They're Spectacular

I recently learned I might serve this spring as a subject expert aboard a cruise ship crossing the Atlantic, as part of an "enrichment program" that provides passengers the opportunity to interact with experts in various fields. I've been identified as an individual who will address "Everything You Wanted to Know about the Weather, Sea and Sky - and Then Some!"

Sounds great. My only real concern was whether I might get sea sick, having never been on an ocean cruise. But then I began thinking about a recent presentation (ppt) on "rouge waves" given by Linwood Vincent, of the U.S. Office of Naval Research, at a meeting of the DC Chapter of the American Meteorological Society. As I thought about Vincent's nightmarish stories and pictures, I worried that sea sickness could be the least of my problems, even if the odds of encountering a rogue wave are extremely small.

Keep reading for more on these monstrous waves...

Technically, rogue waves, sometimes referred to as "freak waves," are defined as waves whose height from wave crest (highest point) to wave trough (lowest point) is more than twice the average height of the largest one-third of waves in a set of measured waves. More simply, as Vincent explained, they are essentially "big waves relative to what you expect to be there."

As described nicely by an article in the New York Times, the two most likely explanations for the occurrence of rogue waves are when smaller waves merge to form large waves, and when storm-generated waves crash into ocean currents coming from the opposite direction.

Vincent cites the example of an oil platform in the North Sea that was experiencing rough but reasonable waves of 13 to 26 feet during a storm on New Year's Day, 1995. Suddenly, seemingly out of nowhere, the platform was hit and extensively damaged by a monstrous wave that instruments measured at more than 80 feet in height (the so-called "Draupner Wave").

Want to go even bigger? In February 2000, scientific instruments onboard a British research west of Scotland measured waves up to 95 feet. More recent (but perhaps somewhat less reliable) observations have recorded wave heights up to 110 feet, about the same height as the Statue of Liberty. Just as important as height is that rogue waves are usually extremely steep. Plowing into one is like hitting a nearly vertical wall of water. If a vessel is lucky enough to survive the initial impact, then coming over the crest is like riding down the steepest incline of the world's tallest roller coaster.

And, by the way, I've never been so scared as my first ride on a roller coaster not too many years ago -- and have not been on one since.

For centuries, these enormous waves had been dismissed as myths. But scientists now recognize these giant wallops of water are far more common and destructive than once imagined. According to Vincent, freak waves are suspected of sinking at least dozens of large ships, including supertankers, while taking hundreds of lives. Freak waves are known to occur in the Great Lakes as well as the oceans. It is believed that just such a wave contributed to the sinking of the freighter SS Edmund_Fitzgerald in May 1975 on Lake Superior. All 29 hands perished in this most famous of Great Lakes disasters.

Cruise liners, at least in recent times, have been more lucky -- if you can call it that -- in their close encounters with rogue waves. In February 1995, the Queen Elizabeth II was slammed by a 95-foot-high wave in the North Atlantic. Captain Ronald Warwick described it as "a great wall of water... it looked as if we were going into the White Cliffs of Dover." But the ship survived with some passengers suffering relatively minor injuries. In April 2005 off the coast of Georgia, the Norwegian Dawn, a 965-foot ocean liner, was struck by a rogue wave estimated at 70 feet high. The wave smashed windows, sent furniture flying, injured four passengers and, not surprisingly, instilled widespread fear and panic.

And the accounts above are only a sampling of the many that have been reported. For example, see: here and here.

The only video of an actual encounter with a rogue wave I'm aware of is the amazing encounter of a 100-foot fishing boat, which was shot for the Discovery Channel's program, "The Deadliest Catch."

As for that gig on the cruise ship, I'll take the advice of my 4-year-old granddaughter: "Don't be scared, Pop-Pop. I didn't get scared when we went sledding last year down the big hill." How could I not go after that kind pep talk? And besides, running into a rogue wave is even less likely than being swept up by a tornado or hit by lightning. But I'll be sure to pack the sea-sickness pills, and probably not mention rogue waves to the passengers.

French join Canadians in Atlantic search of French crew

HALIFAX - A French naval reserve vessel has joined Canadian crews searching for survivors of a French-owned vessel that capsized and sank near the south coast of Newfoundland on Tuesday.

There were four people on board the 30-metre Cap Blanc when it went down about 16 kilometres south of Marystown, N.L. on the Burin Peninsula.

But officials said Wednesday the chance of finding survivors was growing slim. It's not known whether the crew were wearing survival suits.

Meanwhile, another rescue centre spokeswoman denied a French media report that Canadian divers had heard noises inside the vessel before it sank in about 100 metres of water at 2 p.m. local time.

Jeri Grychowski said there was no truth to the report.

The vessel was reported overdue Tuesday after departing Argentia, N.L. for the 12-hour voyage to its home port on the French islands of St-Pierre-Miquelon, off Newfoundland's south coast.

Searchers have found an empty life-raft and a life preserver, but no sign of survivors or other wreckage on the surface. The Cap Blanc was known to have carried two life-rafts.

On Wednesday, a Cormorant helicopter from Gander, N.L. continued the search, along with two coast guard vessels and the French naval ship, Fulmar.

St-Pierre is 20 kilometres off the southern tip of the Burin Peninsula, and the drama unfolding nearby is riveting many on the island of 6,500.

Finding the boat overturned in the water delivered a strong blow to the community, wrote St-Pierre magazine Mathurin on its website.

"There is an immense sadness, of a kind felt by ocean communities struck to the heart by an implacable sea," wrote author Henri Lafitte. "The wait continues until the limits of hope."

RS

![Validate my RSS feed [Valid RSS]](valid-rss.png)