Research team proposes new link to tropical African climate

Research team proposes new link to tropical African climate The Lake Tanganyika area, in southeast Africa, is home to nearly 130 million people living in four countries that bound the lake, the second deepest on Earth.

Scientists have known that the region experiences dramatic wet and dry spells, and that rainfall profoundly affects the area's people, who depend on it for agriculture, drinking water and hydroelectric power.

Scientists thought they knew what caused those rains: a season-following belt of clouds along the equator known as the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ). Specifically, they believed the ITCZ and rainfall and temperature patterns in the Lake Tanganyika area marched more or less in lockstep. When the ITCZ moved north of the equator during the northern summer, the heat (and moisture) would follow, depriving southeast Africa of moisture and rainfall. When the ITCZ moved south of the equator during the northern winter, the moisture followed, and southeast Africa got rain.

Now a Brown-led research team has discovered the ITCZ may not be the key to southeast Africa's climate after all. Examining data from core sediments taken from Lake Tanganyika covering the last 60,000 years, the researchers report in this week's Science Express that the region's climate instead appears to be linked with ocean and atmospheric patterns in the Northern Hemisphere. The finding underscores the interconnectedness of the Earth's climate - how weather in one part of the planet can affect local conditions half a world away.

The discovery also could help scientists understand how tropical Africa will respond to global warming, said Jessica Tierney, a graduate student in Brown's Geological Sciences Department and the paper's lead author.

"It just implies the sensitivity of rainfall in eastern Africa is really high," Tierney said. "It doesn't really take much to tip it."

The researchers, including James Russell and Yongsong Huang of Brown's Department of Geological Sciences faculty and scientists at the University of Arizona and the Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research, identified several time periods in which rainfall and temperature in southeast Africa did not correspond with the ITCZ's location. One such period was the early Holocene, extending roughly from 11,000 years ago to 6,000 years ago, in which the ITCZ's location north of the equator would have meant that tropical Africa would have been relatively dry. Instead, the team's core samples showed the region had been wet.

Two other notable periods - about 34,000 years ago and about 58,000 years ago - showed similar discrepancies, the scientists reported.

In addition, the team found climatic changes that occurred during stadials (cold snaps that occur during glacial periods), such as during the Younger Dryas, suddenly swung rainfall patterns in southeast Africa. Some of those swings occurred in less than 300 years, the team reported.

"That's really fast," Tierney noted, adding it shows precipitation in the region is "jumpy" and could react abruptly to changes wrought by global warming.

While the scientists concluded the ITCZ is not the dominant player in shaping tropical African climate, they say more research is needed to determine what drives rainfall and temperature patterns there. They suspect that a combination of winter winds in northern Asia and sea surface temperatures in the Indian Ocean have something to do with it. Under this scenario, the winds emanating from Asia would pick up moisture from the Indian Ocean as they swept southward toward tropical Africa. The warmer the waters the winds passed over, the more moisture would be gathered, and thus, more rain would fall in southeast Africa. The theory would help explain the dry conditions in southeast Africa during the stadials, Tierney and Russell said, because Indian Ocean surface temperatures would be cooler, and less moisture would be picked up by the prevailing winds.

"What happens in southeast Africa appears to be really sensitive to the Indian Ocean's climate," Russell said.

The team examined past temperature in the region using a proxy called TEX86, developed by the Dutch contributing authors. To measure past precipitation, the researchers examined fatty acid compounds contained in plant leaf waxes stored in lakebed sediments - a relatively new proxy but considered by scientists to be a reliable gauge of charting past rainfall.

Note: This story has been adapted from a news release issued by Brown University

WEATHER NOTE

The Al Gilkes column – Storm chasing in US

It was the start of my annual holiday with my two sons up North. And as the plane climbed thousands of feet into the vast blue skies, I reclined my seat, stretched my feet out to their fullest extent, afforded by the extra leg room of an emergency exist, closed my eyes for a moment and allowed my mind and body to slowly drain themselves of all stresses.

I prayed that Barbados and the other countries in the region would be spared the ravage of tropical storms and hurricanes while I was away. The truth is I did not want a repeat of what happened three years ago when I broke my holiday to rush back home to prepare for the onset of a hurricane.

I vividly recalled how on that occasion every prediction and projection showed Barbados squarely in the direct path of the massive system that was churning its way westward across the Atlantic threatening death and destruction on an unknown scale.

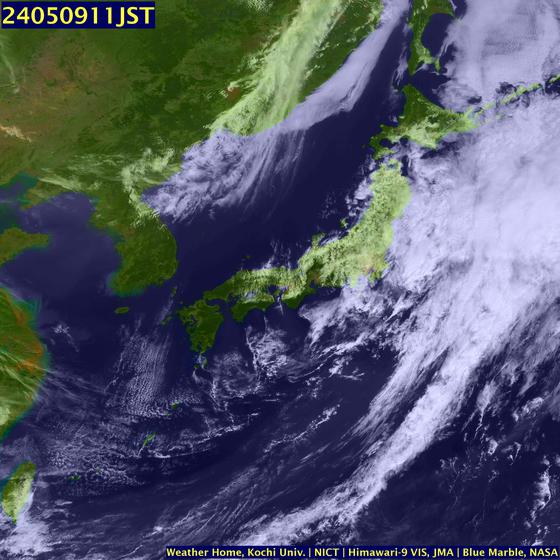

I will never forget how after watching satellite imagery on TV, which showed the outer bands of clouds already in the vicinity of the island and hearing the American forecaster confidently predict that Barbados would start to feel the full fury by nightfall the next day, I called the airline and booked myself on the next direct flight home.

What mattered then was that my relatives, friends, and all of Barbados were under the threat of hurricane force winds and flooding rain and there was no way I could enjoy the party while that was happening.

Fortunately, as has been the case repeatedly since 1956 when many lives were lost and the island suffered millions of dollars in destruction of property, crops, and infrastructure, by the time I landed at Grantley Adams in the early evening, the hurricane watch had been discontinued after the system shifted gears and switched to another route.

But the saying goes that what ain't catch yuh ain't pass you; and so it was that while relaxing in Boston the second Thursday I was there, I clicked the Weather Channel icon on my laptop's desktop to see what was and what was not only to discover that a storm warning had been issued – not for Barbados but for Massachusetts where I was.

That's right. Hanna was about to blow ashore with 70 mph winds on the Carolina coast the next day, then race up the Atlantic Coast, reaching New England by Sunday morning.

By the Saturday night, the storm, which was blamed for disastrous flooding and more than 100 deaths in Haiti, was dumping tonnes of rain on Boston with some cruel thunder and lighting. However, the movement over land had robbed it of any meaningful wind speeds and apart from flooding in some areas there were no reports of roofs being blown off or of any other damage normally associated with strong storms.

Never would I have believed before then that a tropical storm would follow me from Barbados all the way up north to Boston.

Severe Storms Research Center Boosts Defenses Against Twisters

The tornado that ripped through downtown Atlanta on March 14, 2008, produced a death, psychological shock and some $150 million in damage. Yet it was hardly an isolated event.

Georgia ranks high among tornado-plagued areas of the United States. It was 18th among the most affected states between 1953 and 2004. And in 2007, Georgia experienced 42 twisters; only seven states suffered more hits.

Helping to protect Georgia residents against such violent weather is the job of the researchers of the Severe Storms Research Center (SSRC) at the Georgia Tech Research Institute (GTRI). One of their tasks: to explore and develop new technologies able to improve both the accuracy and the timeliness of tornado warnings.

Currently, NEXRAD Doppler radar technology is state-of-the-art in the U.S., which is ravaged by more tornadoes than anyplace else on Earth. NEXRAD offers about a 15-minute average advance warning that a tornado may hit.

"That’s a big improvement over the old days, when a funnel cloud on the horizon was often the first warning,” said John Trostel, deputy director of the SSRC. “Before NEXRAD was established in the 1990s, you would have been lucky to have gotten a 30-second warning.”

The GTRI center was founded after a tornado struck Gainesville, Ga., with no warning in March 1998, leaving 11 people dead in Hall County, recalls SSRC Director Gene Greneker. A task force formed by then-Georgia Gov. Zell Miller recommended a severe-storms center with several missions, including conducting cutting-edge research, collecting and archiving storm data and improving detection and warning. The center was initially funded through the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), and on-going support has come through the state of Georgia with the continuing involvement of the Georgia Emergency Management Agency (GEMA).

"Part of our goal is to explore what’s different about the severe storms of north Georgia,” Greneker said. “Tornadoes in Georgia are often short-lived events that take place over a few minutes, while those in Kansas or Oklahoma may last for an hour.”

NEXRAD continues to be the first line of tornado defense, Greneker explains. Earlier weather radars dating back to the 1950s could sometimes reveal the classic “hook” echo on some tornadoes, but NEXRAD is far more effective.

Today’s national network of NEXRAD stations uses three-dimensional Doppler technology to detect wind direction and other factors; the information shows up on-screen in brightly colored cells that resemble the pixels of a heavily magnified digital photo. When winds in a given area begin to twist in opposite directions - a tornadic phenomenon called wind shear - two cells form a distinctive on-screen “couplet” that alerts weather watchers a tornado may be forming.

SSRC uses several tools to amass and study NEXRAD data, including GR2Analyst software, developed in Georgia, and a WDSS-II analysis station.

"I’m seeing very interesting trends in the number of tornadoes that occur annually in Georgia,” Trostel said. “There was an average of about 15 to 25 events from 1950 through 1970, then a peak in the early 1970s to over 40 events, and then a return to 15 to 25. But since 2000, the trend in the number of annual events appears to be again increasing.”

New Insights into Tornadoes

NEXRAD is an important tool, Trostel acknowledges. Yet to increase the weather watcher’s arsenal, and potentially improve warning times and accuracy, GTRI researchers are developing additional approaches to tornado detection and monitoring.

Currently, SSRC studies North Georgia weather using 12 research systems that use a wide variety of instruments, sensors, computers and software, with two more systems under development. Researchers involved in the effort include Greneker, Trostel, Ed Reedy, Tom Perry and Jenny Matthews, as well as a number of students.

Among the SSRC’s top areas of study is the complex role that lightning and acoustics play in North Georgia’s severe storms and in the formation of tornadoes.

Lightning - Researchers based at GTRI’s Cobb County Research Facility are pursuing several approaches that could potentially correlate lightning’s behavior with tornado activity:

Lightning mapping arrays use multiple receiving stations to monitor severe storms as they move through an area. The SSRC and other Atlanta-area weather stations - such as the National Weather Service at Peachtree City - are developing a six-station array that will augment data already coming from an existing array in northern Alabama;

Electric field mills measure the enormous changes in electric fields between fair weather and severe storms, providing important data that can even correlate raindrop size and frequency with other storm parameters;

A lighting polarization ratio station monitors the horizontally and vertically polarized radio-frequency signals created by lightning strokes, providing data on the behavior of cloud- to-cloud and cloud-to-ground lightning. Greater understanding of lightning, especially the less-understood cloud-to-cloud variety, could shed light on tornado formation;

Gamma-ray detectors record the gamma- and X-rays that emanate from lightning strokes, and offer the potential to correlate the appearance of these powerful phenomena with tornado activity.

Acoustic signals - Severe storms emit very low-frequency sounds—in the range of 50 hertz and below, which is analogous to the sonic footprint of an earthquake. Tornado vortices appear to emit these “infra-sounds” in frequencies ranging from 1 hertz down to tenths of a hertz. At the Cobb Country Research Facility, GTRI researchers are building an array of low-frequency sensors that may allow them to identify sonic signatures unique to tornadoes.

Trostel notes that there are myriad ways to study severe storms, many of them surprisingly cost-efficient. He points to a field mill developed by a local high-school student; constructed from such materials as a coffee can, it can detect electrical fields associated with storms.

"This device does a very good job, and it cost $87,” Trostel said. “We want to get Georgia high-school science classes to construct and deploy these detectors - and then we could track storm-related electrical fields as they progress across the state.”

War over water a source of division

Limited water supplies due to a continuing drought and Israeli restrictions are making life even harder for Palestinian farmers For Palestinians the West Bank water crisis is ‘suffocating’ because it affects both families and businesses, ‘whereas Israel is talking about reducing water for recreational purposes, such as ... swimming pools and lawns’ Abdel-Rahman Tamimi

IN THE plains around the village of Bardala, the Israeli-Palestinian tug-of-war over land and water plays itself out in vivid colour. Largely brown Palestinian farms border green fields owned by Jewish settlers, reports Reuters.

Israel and the occupied West Bank have both been hit hard by drought, but Palestinian farmers say Israeli restrictions on their water supplies have made conditions far worse for them than for farmers in nearby Jewish settlements.

In many homes in the West Bank city of Jenin, water has been all but cut off since April. To cope, residents of Jenin and hundreds of villages get their water delivered by truck at sky-high prices.

In US-sponsored peace talks over Palestinian statehood, disputes over water may be overshadowed by more sensitive issues like the future of Jerusalem and refugees. But Palestinian negotiator Saeb Erekat said an accord would be “unthinkable” without agreement on dividing up the region’s water resources. “If you want to have a state, you must have water,” said Palestinian Water Authority chief Shaddad Attili.

In Bardala in the northern Jordan Valley, Ziyad Sawafta says he gets only enough water to plant vegetables and other crops on half his 50ha plot.

To illustrate the disparity, Sawafta, a 60-year-old father of four, points to the thriving citrus grove next door, owned by the Jewish settlement of Mehola and fed with water through a network of irrigation pipes. Sawafta invokes a common Arab saying for illustration. “We get only the ear from the whole camel. The rest of the camel goes to the settlements”.

Israeli Water Authority spokesman Uri Shor said Palestinians get more water than called for under interim peace agreements. He attributed shortages to Palestinians who he said illegally tap into the water system.

Water has long been a scarce resource in the Middle East but the problem is more acute this year. Scant rainfall has further strained supplies already restricted by Israel, which largely controls the West Bank’s three main aquifers.

Water Authority Chief Attili estimated Palestinian farmers in West Bank and Gaza need 250m cu m of water per year purely for irrigation, but get only about 50m cu m a year. The total amount of water that Palestinians get from their own resources and from Israel is estimated at 200m cu m annually.

”People and land are thirsty and we can do little about it,” Attili said.

Palestinian officials say Israel controls some 50 West Bank wells, with a total capacity of 50m cu m per year, directing it mainly to Jewish settlements, which house some 250,000 people.

The Palestinians control about 200 shallow wells in the West Bank, many of them drilled before the 1967 Middle East war in which Israel captured the territory. Those wells produce about 105m cu m per year, but they are meant to supply water to 2.5m Palestinians.

Attili says West Bank Palestinians supplement their own well supplies by buying up to 45m cu m of water from Israel. Another 5m cu m bought from Israel goes to the Gaza Strip, supplementing 50m cu m from an aquifer.

A big part of the problem for Palestinians, officials and human rights groups say, is that the amount of water supplied by Israel, set by quotas in interim peace agreements in the 1990s, has not increased in line with Palestinian population growth.

”That is not fair,” Attili said, adding that the shortages could be alleviated if Israel allowed his authority to drill two or three new wells in the West Bank.

But the Israeli Water Authority believes permitting Palestinians to drill more wells could “ruin” the existing West Bank aquifers. Israeli officials say Palestinians are not the only ones facing water shortages. Underscoring its concerns, Israel’s government has launched a public campaign to discourage residents and businesses from wasting limited supplies.

Head of the Palestinian Hydrology Group Abdel-Rahman Tamimi said there was no comparison between the shortages facing Israelis and those facing Palestinians in the West Bank because some areas do not even have piped water and other areas suffer from irregular access to drinkable water.

He described the West Bank water crisis as ‘suffocating’ because it affects both families and businesses, ‘whereas Israel is talking about reducing water for recreational purposes, such as ... swimming pools and lawns’.

A recent report by the Israeli human rights group B’tselem said Israeli households consumed on average 3.5 times as much water as Palestinian households.

The group attributed the water shortage in Palestinian areas to what it called Israel’s ‘discriminatory’ policy in distributing water resources and restrictions on drilling new wells.

The shortages have translated into brisk business for water delivery trucks in several West Bank areas. Jenin is connected to the water system but dwindling supplies have forced many there to turn to water vendors, whose prices have soared due to heavy demand and limited supply.

A recent UN report found that Palestinians in some of the hardest-hit communities were spending as much as 30%-40% of their income on water delivered by truck. The Israeli Water Authority did not return several calls from Reuters to request similar information about Israeli consumers.

”I have never witnessed such shortage before,” said Hussein Rahhal, a 73-year-old Jenin water vendor, as he stood by his truck in a long queue of similar vehicles waiting to fill their tanks. He added that some Jenin wells have already dried up.

His colleague, Hashem Abdel-Hafith, who nodded in agreement with Rahhal, said he switched off his mobile phone because he could not keep up with callers demanding water.

In Bardala, home to nearly 2,000 Palestinians, farmers remember better days. Bardala had a surplus of water until the late 1970s when Israel drilled three deep wells next to the village’s four shallow wells, causing them to dry up, they said.

Since then, Israel has reduced the amount of water it pumps to Bardala’s farms, from 240 cu m per hour to 140, forcing many to slash production by up to 50% and to choose crops such as aubergine and beans that can survive on one watering per week.

Another Bardala farmer Yousef Sawafta said prices were falling because everyone in the village was planting the same drought-resistant crops. “In the past, one could find all kinds of vegetables throughout the year. It is not the same any more,” he said.

MARITIME NOTE

SALVORS TO PRODUCE BEST PRACTICE GUIDELINES

MARINE salvage companies meeting in Malta this week have decided move ahead rapidly to produce best practice guidelines for Marine Casualty Management. The guidelines will intended to assist governments, shipowners and managers, port authorities and other interests directly involved in ship salvage operations.

For several years the International Salvage Union (ISU) has proposed the production of best practice guidelines for Marine Casualty Management (MCM Guidelines). At its Annual General Meeting in Malta, ISU members endorsed the project to complete guidelines for circulation and use by salvors, shipowners and coastal states worldwide. The intention is to complete the guidelines during 2009.

ISU president Arnold Witte said: “There is existing International Maritime Organization (IMO) guidance on the issue of places of refuge. There is also very general IMO guidance on general issues relating to the control of ships in emergency situations. What is missing is specific, comprehensive guidance on best practice throughout the entire casualty management process. The MCM Guidelines will fill that gap and, in doing so, will sharpen and enhance marine emergency response capabilities worldwide. Our intention is to consult with our maritime industry partners when finalising the guidelines.”

The guidelines will include provisions on: Pre-event preparations for effective response Special considerations relating to specific casualty types (for example, collision, fire, grounding) First response actions (shore-side and salvor mobilisation, together with ship-board response) Preparing and implementing the Salvage Plan Progressing the salvage operation (including pollution prevention and public issues) Re-delivery of the casualty Key factors contributing to successful salvage and pollution prevention

ISU members have also decided to call for publication of Lloyds Form Salvage Awards, including the full text of the Arbitrator’s Reasons. Mr Witte said: “It is important that the Lloyds arbitration system is not only entirely fair to all sides but is also seen to be fair. An open policy on publication, should the parties involved in the particular case agree, would amount to a great advance in demonstrating the impartiality, validity and flexibility of the Lloyds Open Form (LOF) system

RS

![Validate my RSS feed [Valid RSS]](valid-rss.png)

No comments:

Post a Comment