By KRISTI LANGENBACHER Correspondent Sunday, August 05, 2007

A Coast Guard rescue three months ago led to an opportunity to promote international relations this week. Members from Air Station Elizabeth City were invited to tour two Royal Navy ships visiting Norfolk, Va. on Tuesday.

The invitation was the result of a rescue which involved a British citizen three months ago.

An HH-60 helicopter and a C-130 airplane responded to a distress call from a sailboat 200 nautical miles off the coast of North Carolina on May 7. The crews rescued three men from the stormy waters that day.

Members of both aircrews traveled to Norfolk on Tuesday. The HH-60 helicopter crew of Petty Officer Drew Dazzo, Petty Officer Scott Higgins, Lt. j.g. Aaron Nelson and Lt. Cmdr. Nevada Smith attended the event. Lt. Paul Beavis and Petty Officer Marcus Jones, members of the C-130 airplane crew, attended as well.

They traveled to Naval Station Norfolk to tour two ships from Her Majesty's Service, or HMS. The aircrew members met the crews and toured the HMS Illustrious and the HMS Manchester.

The tour was arranged after a survivor who was rescued by the Air Station Elizabeth City crews wrote a letter recognizing the crews for their rescue on May 7. The crews rescued Canadian citizen Rudy Snel, American citizen Jean Pierre de Lutz, and Ben Tye, a British citizen.

Snel's son wrote a letter to Capt. Mike Andres, commanding officer of Air Station Elizabeth City, encouraging formal recognition of the rescue crews. He also sent copies of the letter to several government officials, including President George Bush, British Prime Minister Tony Blair and the British Consulate General's office in Atlanta.

The British Consulate then contacted the air crews.

"Because of the survivors, the British Consulate in Atlanta arranged a tour to thank us for what we did for the British National," said Smith, aircraft commander of the HH-60 helicopter involved in the rescue.

Smith said the tour was also an opportunity to raise public awareness about the Coast Guard, and to promote international relations. He described the British sailors as sociable, friendly and interesting. The aircrews handed out Coast Guard coins and books to the British sailors, and received DVDs about the Royal Navy.

"For us, we got to show the British sailors some Coast Guard people and let them know what we do," Smith said. "And in return, we learned about the Royal Navy and met some really great people."

The men toured the ships, including the search and rescue helicopter, command centers, avionics repair shop and bridge.

Dazzo, the rescue swimmer who pulled the men from the water on May 7, said the experience was an opportunity to see how another country's military operates.

"It was a learning experience because their operations are similar to our Navy, but how they go about doing them is a little bit different," Dazzo said.

He called the rescue the most challenging rescue of his 10 years in the Coast Guard.

"It's probably the rescue I've prepared for my entire career," Dazzo said. "With high winds, rough seas and very low visibility - it's what you train for."

The crews rescued the three men from their partially-inflated life raft after their sailboat capsized twice during Subtropical Storm Andrea.

Dazzo said writing a letter of recognition is one of the many things the survivors have done since the rescue.

"The guys we rescued really want to see us in the limelight," he said. "The exposure they've given us is really amazing."

One of the survivors also wrote a letter to Dazzo's 13-year-old daughter letting her know how fragile life is and how much he appreciated Dazzo's efforts. The same man also sent a balloon bouquet to Dazzo's son on his second birthday.

This guy has gone above and beyond," Dazzo said. "We didn't expect any of this. Just a thank you when we dropped him off out of the helicopter was enough."

Another highlight of the group's tour of the Royal Navy ships was meeting up with members of the U.S. Marine Corps. The British ships were conducting joint training exercises with the U.S. Marines using the curved ramp on the Illustrious for launching Harrier Jump Jets.

The jets use thrust-vectoring for vertical/short takeoff and landing from the curved ramp on the deck of the ship.

"They told me they conducted 150 landings and take-offs in a 14-hour period," Smith said. "That's pretty amazing."

Dazzo called the flight operations that day impressive, and said the design of the ship was interesting as well.

"The bridge and the air operations were open, and together," he said. "That way the ship crew and the aircrews can communicate more effectively."

The HMS Illustrious is an Invincible-class light aircraft carrier home-ported in Portsmouth Harbour in England. The HMS Manchester is a Type 42 guided missile destroyer with a medium-range missile system.

Weather Story- Chicago, Illinois.

Well in Chicago since 1 August its been hot, humid and muggy. Highs ranging between 90 to 113 in Talyorville. Yesterday was no better and we got punched hard by Mother Nature. At one point yesterday (Monday) evening more than 3,000 cloud-to-ground lightning strikes in 10 minutes were recorded, some very impressive especially in parts of the south and western suburbs. DeKalb County was ground zero for the heaviest storms. WGN reported "3.82” of rain fell between 3:50 p.m. and 6:50 pm—2.90” of it in just 30 minutes".

The outlook for today is not much better, NWS already has Flash Flood Warnings out for Cook and Dekalb counties until 2:30PM CST, so lets watch the radar (brought to you by NexLab) and the skys...

Flood Statement National Weather Service Chicago/Romeoville IL 931 AM CDT Tue Aug 7 2007

Winnebago IL-Mchenry IL-Boone IL-Lake IL-Ogle IL-Cook IL-Kane IL- Dekalb IL- 931 AM CDT Tue Aug 7 2007

...The Flood Warning Remains In Effect Until 230 PM CDT For Northern Dekalb...Northern Kane...Northern Cook...Northeastern Ogle...Lake... Boone...Mchenry And Winnebago Counties...

At 931 AM CDT...National Weather Service Doppler Radar Estimates And Rainfall Observers Have Reported A Swath Of 3 To 7 Inches Of Rain That Has Fallen From Southern Winnebago County Eastward Into Central Lake County. The Heaviest Rainfall Reports Have Been In The Rockford Area Where Over 6 Inches Of Rain Has Fallen. Rain Has Subsided This Morning...But Some Roads Remain Closed Due To Flooding.

A Flood Warning Means That Flooding Is Imminent Or Has Been Reported. Stream Rises Will Be Slow And Flash Flooding Is Not Expected. However...All Interested Parties Should Take Necessary Precautions Immediately.

Do Not Drive Your Vehicle Into Areas Where The Water Covers The Roadway. The Water Depth May Be Too Great To Allow Your Car To Cross Safely. Move To Higher Ground.

Do Not Attempt To Cross Water Covered Bridges...Dips...Or Low Water Crossings. Never Try To Cross A Flowing Stream...Even A Small One...On Foot. To Escape Rising Water Move Up To Higher Ground.

Lat...Lon 4220 8939 4216 8928 4212 8921 4205 8906 4199 8894 4199 8853 4201 8766 4220 8781 4235 8785 4238 8781 4248 8780 4249 8939

Stay cool and stay dry!

RS

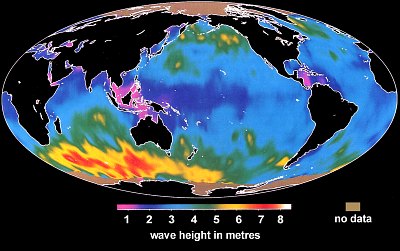

In the diagram some familiar terms are shown. A floating object is observed to move in perfect circles when waves oscillate harmoniously sinus-like in deep water. If that object hovered in the water, like a water particle, it would be moving along diminishing circles, when placed deeper in the water. At a certain depth, the object would stand still. This is the wave's base, precisely half the wave's length. Thus long waves (ocean swell) extend much deeper down than short waves (chop). Waves with 100 metres between crests are common and could just stir the bottom down to a depth of 50m. Note that the depth of a wave has little to do with its height! But a wave's height contains the wave's energy, which is unrelated to the wave's length. Long surface waves travel faster and further than short ones. Note also that the forward movement of the water under a crest in shallow water is faster than the backward movement under its trough. By this difference, sand is swept forward towards the beach.

In the diagram some familiar terms are shown. A floating object is observed to move in perfect circles when waves oscillate harmoniously sinus-like in deep water. If that object hovered in the water, like a water particle, it would be moving along diminishing circles, when placed deeper in the water. At a certain depth, the object would stand still. This is the wave's base, precisely half the wave's length. Thus long waves (ocean swell) extend much deeper down than short waves (chop). Waves with 100 metres between crests are common and could just stir the bottom down to a depth of 50m. Note that the depth of a wave has little to do with its height! But a wave's height contains the wave's energy, which is unrelated to the wave's length. Long surface waves travel faster and further than short ones. Note also that the forward movement of the water under a crest in shallow water is faster than the backward movement under its trough. By this difference, sand is swept forward towards the beach.

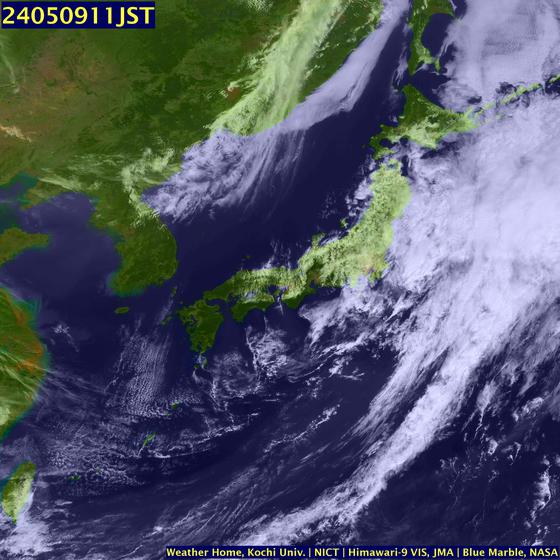

The biggest waves on the planet are found where strong winds consistently blow in a constant direction. Such a place is found south of the Indian Ocean, at latitudes of -40º to -60º, as shown by the yellow and red colours on this satellite map. Waves here average 7m, with the occasional waves twice that height! Directly south of New Zealand, wave heights exceeding 5m are also normal. The lowest waves occur where wind speeds are lowest, around the equator, particularly where the wind's fetch is limited by islands, indicated by the pink colour on this map. However, in these places, the sea water warms up, causing the birth of tropical cyclones, typhoons or hurricanes, which may send large waves in all directions, particularly in the direction they are travelling.

The biggest waves on the planet are found where strong winds consistently blow in a constant direction. Such a place is found south of the Indian Ocean, at latitudes of -40º to -60º, as shown by the yellow and red colours on this satellite map. Waves here average 7m, with the occasional waves twice that height! Directly south of New Zealand, wave heights exceeding 5m are also normal. The lowest waves occur where wind speeds are lowest, around the equator, particularly where the wind's fetch is limited by islands, indicated by the pink colour on this map. However, in these places, the sea water warms up, causing the birth of tropical cyclones, typhoons or hurricanes, which may send large waves in all directions, particularly in the direction they are travelling.

By late afternoon the winds were sustained at well over 70 knots and seas were building fast. I estimate seas were well into 25 feet by dusk but after adding approximately 150 feet of drogue line the vessel handled smoothly over the next eight hours advancing with the seas at about 6 knots (SOG). By late evening the winds were sustained above 74 kts and a crew member recorded a peak of 85.5 kts.

By late afternoon the winds were sustained at well over 70 knots and seas were building fast. I estimate seas were well into 25 feet by dusk but after adding approximately 150 feet of drogue line the vessel handled smoothly over the next eight hours advancing with the seas at about 6 knots (SOG). By late evening the winds were sustained above 74 kts and a crew member recorded a peak of 85.5 kts. We became aware of fixed wing overflight sometime between 06:00 and 07:00 hours and estimate that the Coast Guard helicopter arrived some time around 08:30 hours. As seemingly the most affected by hypothermia and almost unconscious the crew had me lifted out first. It was a perilous process during which Coast Guard AST2 Dazzo was himself injured (later to be hospitalized with us). The life raft was destroyed and abandoned by AST2 Dazzo as the third crew member was extracted. He also recouped the GPIRB which remained in USCG custody.

We became aware of fixed wing overflight sometime between 06:00 and 07:00 hours and estimate that the Coast Guard helicopter arrived some time around 08:30 hours. As seemingly the most affected by hypothermia and almost unconscious the crew had me lifted out first. It was a perilous process during which Coast Guard AST2 Dazzo was himself injured (later to be hospitalized with us). The life raft was destroyed and abandoned by AST2 Dazzo as the third crew member was extracted. He also recouped the GPIRB which remained in USCG custody.

![Validate my RSS feed [Valid RSS]](valid-rss.png)